The Fox Theatre and "Mighty Mo'"

by John Clark McCall, Jr.

During a short, furious period of silent movie palace architecture, America saw a campaign of theatre construction that made gold leaf, ponderous chandeliers, and the Mighty Wurlitzer the rule and not the exception. The campaign left its imprint on America’s large urban areas, as well as smaller towns. At best, only the scale was altered.

What, then, makes Atlanta’s Fox Theatre more than just another movie palace, more than simply a relic testifying to the age in which it materialized, and most importantly, a structure that has the merit to stand indefinitely? The reasons are parallel to the history of the original Fox plans…plans that were not actually those of “Fox” at all!

The year 1928 saw a bustling Atlanta, with its own “Great White Way” of theatres – Peachtree Street, with the busy marquee lights of the Metropolitan, Paramount, Georgia, Capitol, Grand, and the new Erlanger. The Atlanta theatre scene was precariously overgrown. However in early 1928, the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine announced plans for new headquarters for their Yaraab Temple. Tom Law, the Shrine’s chief potentate, charged Atlanta architects Marye, Alger, and Vinour to design a lasting monument that would out-Baghdad Baghdad. Their plans ultimately called for a 200 by 400-foot edifice of cream and buff-colored brick to house the Temple. The style source was akin to that of the far-Eastern cultures, from a ballroom, offices, retail shops, to the mammoth temple auditorium designed to accommodate nearly 5,000 loyal followers. Unfortunately, before the ink was dry on the blueprints it became obvious that the first prayer tower would never be raised unless sufficient funds could be secured to finance construction the estimated three million dollar edifice.

Fortunately, movie mogul, William K. Fox, riding high on his theatre and motion picture Empire, was in the midst of establishing six new super picture palaces throughout the country, including two Siamese/Burmese twins in St. Louis and Detroit. With the scheme of far-Eastern flavor lavished on these two theatres, the proposed Atlanta Yaraab Temple’s architecture seemed right in step. So, the Shrine negotiated a 21-year lease agreement with The Fox Theatre Corporation for the auditorium for use as a movie palace. The Shriners, in turn, gained construction money, executive offices, and the use of the auditorium for at least six times yearly for ceremonies, initiations, and special feast days.

William Fox moved in, or rather his inventive wife Eve did, and began a campaign of furnishing the house, while saving the Fox Theatre Corporation untold decorators’ fees. The resourceful Eve Fox brought to the Fox’s interior a sampling of styles associated with the Turks and Egyptians. The true-to-style treatment of the auditorium consisting of a faux courtyard surrounded by structure, rather than being in an auditorium, whose interior is smothered with an assortment of ornamental devices and fabric, gives the theatre a look of timeless establishment and good taste. Furthermore, the Atlanta Fox has a real rationale for its far-Eastern design (as a shrine), unlike most structures built strictly as theatres.

The Fox’s exterior treatment should receive the first accolade. Few American theatres have a building site that allows the architects to design more than just a front façade. The Fox exterior is a testament to Eastern design with courses of cream and buff brick supplanted with sections of tile, tabby, and domed minarets giving the theatre an expectation of the magic to be found inside. Originally, the Shrine’s main entrance was to be in the Ponce de Leon Avenue frontage through an arabesque entrance under the largest of the Fox “onion” domes. However, William Fox preferred a Peachtree Street entrance as he thought Peachtree Street provided a more spectacular entry. This entry is through a 140-foot-deep loggia lined with display windows and providing access to the theatre lobby and the main entrance to the Egyptian Ballroom. Various textured plaster reliefs, filigreed lamps, tile and terrazzo flooring all serve as a prelude for what is to come and contribute to captivating and protecting the next show’s patrons.

The vast ambience afforded the over 65,000 square foot auditorium proper is not realized until midway at the orchestra level, at the underside of the balcony. Here lies an open view of the Fox’s atmospheric ceiling treatment, a view of the immense depth of the balcony dress circle, and the proscenium arch. The sides of the auditorium are treated as castellated walls with dimly lit barred windows, minarets, and devices associated with a far-Eastern fortress. Overhead, the Fox’s very believable “stars and moving clouds” attest to the architects’ study of correct stellar groupings and atmospheric conditions. Flanking either side of the stage are the warmest and most ornamental features of the auditorium – pierced gold-finished organ grilles, visually “supported” by false balconettes at their base. Unlike many atmospheric houses, the Fox’s sky area ends long before the stage opening at an arched bridge lined with lanterns and oriental rugs, presumably draped over the bridge’s railing for market day. Obviously, much of the Fox’s intrigue rests with its infinite detail and its endless features of innovation and design while possessing a strong, unified appearance. Indeed the Fox also excels in a technical sense with superior traffic pattern design, sight lines, acoustics, and audience comfort. And if a theatre organ ever profited from the planning that went into the “envelope”, the Fox Möller organ does!

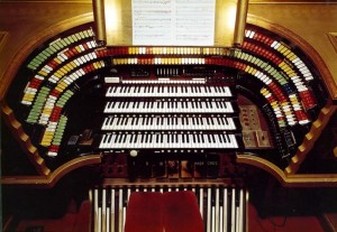

The Fox opened in December, 1929 and was quite a Christmas gift to Atlantans. No theatre historian has been able to match the excitement of the late author and ATOS member Ben Hall’s written and verbal accounts of American theatre openings. His treatise on the Atlanta Fox is no exception. In jacket notes for the Fox’s first commercial organ recording, Here With the Wind featuring Bob Van Camp, Hall wrote: “Promptly at 8:30, the show began. The evening’s next spectacular surprise was revealed as, out of the depths of the orchestra pit, rose the biggest, goldest, and most colorful pipe organ console anyone had ever seen. Almost swallowed by the enormous maw of colored stop tablets and gleaming ivory keyboards was the tiny figure of a woman, Iris Vining Wilkins by name, who launched into a medley of hits of the day at the console of the $80,000 Mammoth Moller Pipe Organ…”

But the great Fox empire itself was soon to collapse and Atlanta’s temple of entertainment was passed around to several companies in the 1930’s and 40’s – and even to the city fathers when back taxes remained unpaid. The Fox persisted with great difficulty, however in January 1, 1951, the Wilby interests, in partnership with Herbert F. Kincey, took over and they brought in Noble K. Arnold to manage the Fox. Under his management, the theatre experienced its most prosperous years as a motion picture theatre. Upon coming to the Fox in 1951, Arnold turned immediately to the Fox’s 4/42 Möller languishing in the pit. A hasty restoration was made, and organist Eddie Ford was signed as staff artist. No systematic upkeep was employed for the instrument however, and by 1954, the organ was again in drastic need of repair and was last heard publicly for nearly ten years.

Over the years the theatre made a gradual changeover to family fare movies as a rule, paralleling the policy of New York City’s Radio City Music Hall. While this worked for a while for the Fox, ultimately the Fox’s clientele changed, and moreover, attendance continued to decline. There were a few premieres, a film festival, and some rock venues that almost destroyed some of the Fox’s finest interior fitting. Unfortunately, on January 2, 1975, the Atlanta Fox Theatre formally ended its career as a motion picture house and padlocks were placed on the doors.

In the meantime, an organization had already been formed that would ultimately be responsible for saving “Mecca” from the wrecker’s ball. In the summer of 1974, under the leadership of Arnall T. “Pat” Connell and three ATOS members, Joe Patten, Bob Van Camp, and attorney Robert Foreman, Jr., Atlanta Landmarks, Inc. was formed. The organization’s formation came after an interesting and rapid chain of events: lists of names petitioning to save the Fox began to multiply, and Helen Hayes, Mitzi Gaynor, Liberace, and hosts of other notables in the entertainment world came forth with pleas for saving the theatre.

The final arrangements involving lengthy and complex negotiations permitted Atlanta Landmarks, Inc. to acquire ownership of the Fox and on June 25, 1975 Atlanta Landmarks became the new owner of the Fox. The total amount of funds to be raised in order to save the Fox was $2,400,000. The Fox’s salvation call fell squarely at the feet of Atlanta’s citizens, and this city whose very symbol shows a Phoenix rising from the ashes, “resurged”, and Mecca was saved! At the forefront of this citizenry were hard-working members of the Southeastern (later re-chartered as “Atlanta”) Chapter of ATOS.

Atlanta Landmarks and now Fox Theatre, Inc. has become a model operation, often studied and copied by other cities having significant theatres and other structures. In 1978, Landmarks paid off the original mortgage six months early. In 1979, the Fox’s three-month run of A Chorus Line broke national records with over $1 million at the box office. 1985 brought discretely installed state-of-the-art systems for improved sound and lighting, leading to a second major fund raising campaign in 1987 which netted $4.2 million to bring further restoration and improvements to the Fox. In 1988, the Fox Theatre was named the number one grossing theatre in the 3,000 to 5,000-seat segment of the entertainment industry in the United States.

The Fox now boasts many outreach programs, including the Fox Theatre Institute which has assisted other theatres in Georgia, including the Rylander in Americus and the Grand in Fitzgerald. Looking back to those dark days when the Atlanta ATOS Chapter thought that a December concert by Lyn Larsen might be the grand finale, these facts and figures seem almost surreal.

Restoration of Fox Möller organ was begun after a meeting with Noble Arnold and the American Theatre Organ Enthusiasts’ President “Tiny” James and Regional Vice-President Erwin Young in December, 1962. In 1963, a small group of Southeastern Chapter (now Atlanta Chapter) ATOE (now ATOS) volunteers, under the direction of Joe G. Patten, began a thorough cleaning and restoration program on the instrument. Since that time the organ has received attention from some of the finest pipe organ technicians, but none more dedicated, able, or caring than ATOS Lifetime Member, Joe Patten. On Thanksgiving Day, November 28, 1963 the Fox Möller again rose to glory, with Bob Van Camp playing “Georgia on My Mind”.

This organ, even in the eyes of the general public, remains unchallenged as the Fox’s single greatest asset. With four manuals and 42 ranks of pipes in five chambers, the organ reigned for three years (1929 -1932) as the largest theatre organ in the world. The Wurlitzer in New York City’s Radio City Music Hall received the trophy after opening its doors on December 27, 1932, and, as most enthusiasts know, new records have been set for the size of theatre organs if the universe includes installations outside of public theatres!

Excepting a few mechanical modifications, new console coachwork (that now replicates the original console design in all its gold-leafed splendor), the addition of the grand piano from Chicago’s Piccadilly Theatre, and adding a 32’ pedal complement to the specifications, the Fox organ remains as one of the most original installations in the world. In a fitting tribute, ATOS has named it to the National Registry of Significant Instruments.

Through the years, Fox organists of the “golden era” included Iris Vining Wilkins (1929), Jimmy Beers (1931-33), Eddie Ford (1951), Cliff Cameron (1941), “Smilin” Al Evans (1930-32), Arthur Goebel, Don Mathis (1944), “organace” Dwight Brown, Homer Knowles (1943), Stanleigh Malotte, and Graham Jackson. The Renaissance for theatre organ in the early 1960’s brought us Bob Van Camp, Lee Erwin, Billy Nalle, and paved the way for later impresarios like Lyn Larsen, Hector Olivera, John Seng, and Virgil Fox. In 2004, ATOS and the Atlanta Chapter presented the Fabulous Fox Organ Weekend fetching the talents of Simon Gledhill, Richard Hills, Lyn Larsen, Walt Strony, and Clark Wilson. And, of course, the great George Wright did actually play the organ in a private session.

The irrevocable status of the Fox as a jewel in the crown of movie palaces has also insured that the Fox Möller will always be one of its most important features. Few instruments have ever had better name recognition with the general public than “Mighty Mo”.

During a short, furious period of silent movie palace architecture, America saw a campaign of theatre construction that made gold leaf, ponderous chandeliers, and the Mighty Wurlitzer the rule and not the exception. The campaign left its imprint on America’s large urban areas, as well as smaller towns. At best, only the scale was altered.

What, then, makes Atlanta’s Fox Theatre more than just another movie palace, more than simply a relic testifying to the age in which it materialized, and most importantly, a structure that has the merit to stand indefinitely? The reasons are parallel to the history of the original Fox plans…plans that were not actually those of “Fox” at all!

The year 1928 saw a bustling Atlanta, with its own “Great White Way” of theatres – Peachtree Street, with the busy marquee lights of the Metropolitan, Paramount, Georgia, Capitol, Grand, and the new Erlanger. The Atlanta theatre scene was precariously overgrown. However in early 1928, the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine announced plans for new headquarters for their Yaraab Temple. Tom Law, the Shrine’s chief potentate, charged Atlanta architects Marye, Alger, and Vinour to design a lasting monument that would out-Baghdad Baghdad. Their plans ultimately called for a 200 by 400-foot edifice of cream and buff-colored brick to house the Temple. The style source was akin to that of the far-Eastern cultures, from a ballroom, offices, retail shops, to the mammoth temple auditorium designed to accommodate nearly 5,000 loyal followers. Unfortunately, before the ink was dry on the blueprints it became obvious that the first prayer tower would never be raised unless sufficient funds could be secured to finance construction the estimated three million dollar edifice.

Fortunately, movie mogul, William K. Fox, riding high on his theatre and motion picture Empire, was in the midst of establishing six new super picture palaces throughout the country, including two Siamese/Burmese twins in St. Louis and Detroit. With the scheme of far-Eastern flavor lavished on these two theatres, the proposed Atlanta Yaraab Temple’s architecture seemed right in step. So, the Shrine negotiated a 21-year lease agreement with The Fox Theatre Corporation for the auditorium for use as a movie palace. The Shriners, in turn, gained construction money, executive offices, and the use of the auditorium for at least six times yearly for ceremonies, initiations, and special feast days.

William Fox moved in, or rather his inventive wife Eve did, and began a campaign of furnishing the house, while saving the Fox Theatre Corporation untold decorators’ fees. The resourceful Eve Fox brought to the Fox’s interior a sampling of styles associated with the Turks and Egyptians. The true-to-style treatment of the auditorium consisting of a faux courtyard surrounded by structure, rather than being in an auditorium, whose interior is smothered with an assortment of ornamental devices and fabric, gives the theatre a look of timeless establishment and good taste. Furthermore, the Atlanta Fox has a real rationale for its far-Eastern design (as a shrine), unlike most structures built strictly as theatres.

The Fox’s exterior treatment should receive the first accolade. Few American theatres have a building site that allows the architects to design more than just a front façade. The Fox exterior is a testament to Eastern design with courses of cream and buff brick supplanted with sections of tile, tabby, and domed minarets giving the theatre an expectation of the magic to be found inside. Originally, the Shrine’s main entrance was to be in the Ponce de Leon Avenue frontage through an arabesque entrance under the largest of the Fox “onion” domes. However, William Fox preferred a Peachtree Street entrance as he thought Peachtree Street provided a more spectacular entry. This entry is through a 140-foot-deep loggia lined with display windows and providing access to the theatre lobby and the main entrance to the Egyptian Ballroom. Various textured plaster reliefs, filigreed lamps, tile and terrazzo flooring all serve as a prelude for what is to come and contribute to captivating and protecting the next show’s patrons.

The vast ambience afforded the over 65,000 square foot auditorium proper is not realized until midway at the orchestra level, at the underside of the balcony. Here lies an open view of the Fox’s atmospheric ceiling treatment, a view of the immense depth of the balcony dress circle, and the proscenium arch. The sides of the auditorium are treated as castellated walls with dimly lit barred windows, minarets, and devices associated with a far-Eastern fortress. Overhead, the Fox’s very believable “stars and moving clouds” attest to the architects’ study of correct stellar groupings and atmospheric conditions. Flanking either side of the stage are the warmest and most ornamental features of the auditorium – pierced gold-finished organ grilles, visually “supported” by false balconettes at their base. Unlike many atmospheric houses, the Fox’s sky area ends long before the stage opening at an arched bridge lined with lanterns and oriental rugs, presumably draped over the bridge’s railing for market day. Obviously, much of the Fox’s intrigue rests with its infinite detail and its endless features of innovation and design while possessing a strong, unified appearance. Indeed the Fox also excels in a technical sense with superior traffic pattern design, sight lines, acoustics, and audience comfort. And if a theatre organ ever profited from the planning that went into the “envelope”, the Fox Möller organ does!

The Fox opened in December, 1929 and was quite a Christmas gift to Atlantans. No theatre historian has been able to match the excitement of the late author and ATOS member Ben Hall’s written and verbal accounts of American theatre openings. His treatise on the Atlanta Fox is no exception. In jacket notes for the Fox’s first commercial organ recording, Here With the Wind featuring Bob Van Camp, Hall wrote: “Promptly at 8:30, the show began. The evening’s next spectacular surprise was revealed as, out of the depths of the orchestra pit, rose the biggest, goldest, and most colorful pipe organ console anyone had ever seen. Almost swallowed by the enormous maw of colored stop tablets and gleaming ivory keyboards was the tiny figure of a woman, Iris Vining Wilkins by name, who launched into a medley of hits of the day at the console of the $80,000 Mammoth Moller Pipe Organ…”

But the great Fox empire itself was soon to collapse and Atlanta’s temple of entertainment was passed around to several companies in the 1930’s and 40’s – and even to the city fathers when back taxes remained unpaid. The Fox persisted with great difficulty, however in January 1, 1951, the Wilby interests, in partnership with Herbert F. Kincey, took over and they brought in Noble K. Arnold to manage the Fox. Under his management, the theatre experienced its most prosperous years as a motion picture theatre. Upon coming to the Fox in 1951, Arnold turned immediately to the Fox’s 4/42 Möller languishing in the pit. A hasty restoration was made, and organist Eddie Ford was signed as staff artist. No systematic upkeep was employed for the instrument however, and by 1954, the organ was again in drastic need of repair and was last heard publicly for nearly ten years.

Over the years the theatre made a gradual changeover to family fare movies as a rule, paralleling the policy of New York City’s Radio City Music Hall. While this worked for a while for the Fox, ultimately the Fox’s clientele changed, and moreover, attendance continued to decline. There were a few premieres, a film festival, and some rock venues that almost destroyed some of the Fox’s finest interior fitting. Unfortunately, on January 2, 1975, the Atlanta Fox Theatre formally ended its career as a motion picture house and padlocks were placed on the doors.

In the meantime, an organization had already been formed that would ultimately be responsible for saving “Mecca” from the wrecker’s ball. In the summer of 1974, under the leadership of Arnall T. “Pat” Connell and three ATOS members, Joe Patten, Bob Van Camp, and attorney Robert Foreman, Jr., Atlanta Landmarks, Inc. was formed. The organization’s formation came after an interesting and rapid chain of events: lists of names petitioning to save the Fox began to multiply, and Helen Hayes, Mitzi Gaynor, Liberace, and hosts of other notables in the entertainment world came forth with pleas for saving the theatre.

The final arrangements involving lengthy and complex negotiations permitted Atlanta Landmarks, Inc. to acquire ownership of the Fox and on June 25, 1975 Atlanta Landmarks became the new owner of the Fox. The total amount of funds to be raised in order to save the Fox was $2,400,000. The Fox’s salvation call fell squarely at the feet of Atlanta’s citizens, and this city whose very symbol shows a Phoenix rising from the ashes, “resurged”, and Mecca was saved! At the forefront of this citizenry were hard-working members of the Southeastern (later re-chartered as “Atlanta”) Chapter of ATOS.

Atlanta Landmarks and now Fox Theatre, Inc. has become a model operation, often studied and copied by other cities having significant theatres and other structures. In 1978, Landmarks paid off the original mortgage six months early. In 1979, the Fox’s three-month run of A Chorus Line broke national records with over $1 million at the box office. 1985 brought discretely installed state-of-the-art systems for improved sound and lighting, leading to a second major fund raising campaign in 1987 which netted $4.2 million to bring further restoration and improvements to the Fox. In 1988, the Fox Theatre was named the number one grossing theatre in the 3,000 to 5,000-seat segment of the entertainment industry in the United States.

The Fox now boasts many outreach programs, including the Fox Theatre Institute which has assisted other theatres in Georgia, including the Rylander in Americus and the Grand in Fitzgerald. Looking back to those dark days when the Atlanta ATOS Chapter thought that a December concert by Lyn Larsen might be the grand finale, these facts and figures seem almost surreal.

Restoration of Fox Möller organ was begun after a meeting with Noble Arnold and the American Theatre Organ Enthusiasts’ President “Tiny” James and Regional Vice-President Erwin Young in December, 1962. In 1963, a small group of Southeastern Chapter (now Atlanta Chapter) ATOE (now ATOS) volunteers, under the direction of Joe G. Patten, began a thorough cleaning and restoration program on the instrument. Since that time the organ has received attention from some of the finest pipe organ technicians, but none more dedicated, able, or caring than ATOS Lifetime Member, Joe Patten. On Thanksgiving Day, November 28, 1963 the Fox Möller again rose to glory, with Bob Van Camp playing “Georgia on My Mind”.

This organ, even in the eyes of the general public, remains unchallenged as the Fox’s single greatest asset. With four manuals and 42 ranks of pipes in five chambers, the organ reigned for three years (1929 -1932) as the largest theatre organ in the world. The Wurlitzer in New York City’s Radio City Music Hall received the trophy after opening its doors on December 27, 1932, and, as most enthusiasts know, new records have been set for the size of theatre organs if the universe includes installations outside of public theatres!

Excepting a few mechanical modifications, new console coachwork (that now replicates the original console design in all its gold-leafed splendor), the addition of the grand piano from Chicago’s Piccadilly Theatre, and adding a 32’ pedal complement to the specifications, the Fox organ remains as one of the most original installations in the world. In a fitting tribute, ATOS has named it to the National Registry of Significant Instruments.

Through the years, Fox organists of the “golden era” included Iris Vining Wilkins (1929), Jimmy Beers (1931-33), Eddie Ford (1951), Cliff Cameron (1941), “Smilin” Al Evans (1930-32), Arthur Goebel, Don Mathis (1944), “organace” Dwight Brown, Homer Knowles (1943), Stanleigh Malotte, and Graham Jackson. The Renaissance for theatre organ in the early 1960’s brought us Bob Van Camp, Lee Erwin, Billy Nalle, and paved the way for later impresarios like Lyn Larsen, Hector Olivera, John Seng, and Virgil Fox. In 2004, ATOS and the Atlanta Chapter presented the Fabulous Fox Organ Weekend fetching the talents of Simon Gledhill, Richard Hills, Lyn Larsen, Walt Strony, and Clark Wilson. And, of course, the great George Wright did actually play the organ in a private session.

The irrevocable status of the Fox as a jewel in the crown of movie palaces has also insured that the Fox Möller will always be one of its most important features. Few instruments have ever had better name recognition with the general public than “Mighty Mo”.